Remembering 2004 - pt. 1

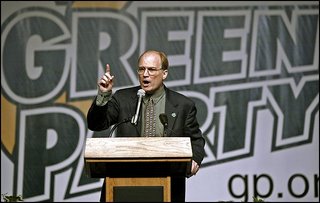

With the Green Party of the United States having its national meeting this weekend (in Tucson, AZ), it may be a good time to (re)consider the 2004 convention fight between David Cobb (above) and Ralph Nader.

With the Green Party of the United States having its national meeting this weekend (in Tucson, AZ), it may be a good time to (re)consider the 2004 convention fight between David Cobb (above) and Ralph Nader.As I noted earlier, I've started reading Independent Politics: The Green Party Strategy Debate, a reader edited by Howie Hawkins. Hawkins, a New York Green, was strongly in the Nader camp, and this book is part of the ongoing post-election spin. This book presents both sides of the argument, by reprinting documents and essays from notable participants, including Californians Peter Camejo, Todd Chretien, Matt Gonzalez, Forrest Hill, Donna Warren, and the late Walt Sheasby.

So far, I've only read Hawkins' introduction, which is nearly 40 pages. But here is my initial reaction: I'm not convinced. I didn't think the Green Party should run a candidate in 2004--certainly not a non-Green who had already run twice on the ticket and refused to face a primary challenge--and I stand behind that conviction.

Nader's supporters from 2004 have tried to frame the debate as one of independence from the Democrats vs. support for the Democrats. In this dichotomy, Nader is the independent, anti-war candidate, and Cobb is the pro-Kerry, not clearly anti-war candidate. To accomplish this, Hawkins makes two arguments: first, that Cobb, by not campaigning in states expected to be up for grabs on election day, was essentially endorsing Kerry; and second, that Kerry and Bush were essentially equivalent.

Although I believed, in 2000, that Gore was about as bad as Bush, in 2004 I found the argument offensive. Bush was much worse than anyone could have imagined. Kerry may have shied away from an anti-Iraq-war message, and certainly supported the war in Afghanistan, he would not have gotten us into the mess in Iraq in the first place, and was not nearly the incompetent that Bush is. But Nader and his running mate, Camejo, in their attempt to find support in the polarized electorate, went even farther than equivalating Kerry and Bush. They actively demonized Kerry and the Democrats every chance they got. In criticizing the Anybody But Bush (ABB) coalition, they at times sounded like Anybody But Kerry.

Although I believed, in 2000, that Gore was about as bad as Bush, in 2004 I found the argument offensive. Bush was much worse than anyone could have imagined. Kerry may have shied away from an anti-Iraq-war message, and certainly supported the war in Afghanistan, he would not have gotten us into the mess in Iraq in the first place, and was not nearly the incompetent that Bush is. But Nader and his running mate, Camejo, in their attempt to find support in the polarized electorate, went even farther than equivalating Kerry and Bush. They actively demonized Kerry and the Democrats every chance they got. In criticizing the Anybody But Bush (ABB) coalition, they at times sounded like Anybody But Kerry.One of the valid criticisms of the 2004 convention is of the method for giving states representation. The formula gives small states a disproportionate percentage of delegates. This is a hard issue to solve, given that people in many states do not have the ability to register Green. Ideally, every primary voter would be equal, but many states use conventions that allow only active members to participate. By some calculations, California could have 40 percent of the delegates, instead, it has much fewer.

Nader/Camejo supporters use this as an argument that the convention was illigitimate and that Nader should have been endorsed. "The big parties, notably California and New York, with two-thirds of all the registered Greens in the U.S. between them, voted overwhelmingly for Nader," Hawkins writes. In fact, Nader was not on the ballot in either of these states. The votes Hawkins counts for Nader were cast for "favorite son" candidates. In the case of California, that was Peter Camejo, who was just coming off two state wide campaigns for governor and participation in televised debates. It is not clear at all that primary voters knew they were voting for Nader when they punched the card for Camejo. At this point, Camejo had not been selected as Nader's running mate. Perhaps the voters were tired of running Nader and wanted a fresh face to head the ticket. Perhaps they wanted a strong run by a registered Green. Or perhaps his was the only name they recognized.

Hawkins alleges that leaders in the national party purposely pushed Nader away after the 2000 election. I have no reason to doubt his account, but I don't think it changes the fact that when Nader asked the convention to endorse him, he was doing an end run around the primary process and running as an independent/coalition candidate rather than as the Green Party candidate he was in 1996 and 2000.

In December, 2003, Nader surveyed the landscape and withdrew his name from consideration as the Green presidential candidate. "Nader went on to cite several factors that he felt made a Green run by him impractical," Hawkins writes. "He said the fact that the Greens were waiting until the June 2004 convention before deciding whether to run a candidate and, if so, whether to run safe states or all out, made it difficutl for a serious candidate to raise funds and seek ballot access."

Nader appears to be expecting a coronation, an image that upset many Green activists, who felt the party was ready for a contested primary. Had he worked within the process, rather than expecting an endorsement from the national party leadership, he probably would have picked up the nomination easily, as Hawkins admits: "Had he chosen to seek the Green nomination, it is likely he would have won it and headed up a Green presidential campaign that still had a solid majority of Greens backing him."

Hawkins believes that the Green Party's decision to endorse Cobb, with his safe states strategy, split the party and the anti-war movement. But it can as easily be argued that Nader's decision to run an independent campaign with or without the Green Party was the decisive split. Either way, it is unlikely a united anti-war and anti-corporate party campaign could have had the impact that Hawkins wishes to believe it could have.

Certainly in retrospect, the Anybody But Bush coalition (which included me) was a failure that led to demoralization among Greens and other progressives, but imagine how much animosity a more popular, united Green campaign would have generated when Bush was reelected. In the event, the Democrats had their open shot at Bush and missed. They cannot blame anybody but themselves. And that opens up the door for the Green Party.